The $1 Trillion Hardware Tax: Why the AI Revolution Runs on Blue-Collar Labor

The AI revolution doesn’t live in the "cloud." It lives in sprawling concrete footprints across Northern Virginia’s "Data Center Alley" and the flatlands of West Texas. These structures are not mere warehouses; they are the most complex industrial machines ever built, drawing enough power to light up mid-sized cities and requiring miles of precision-fitted piping.

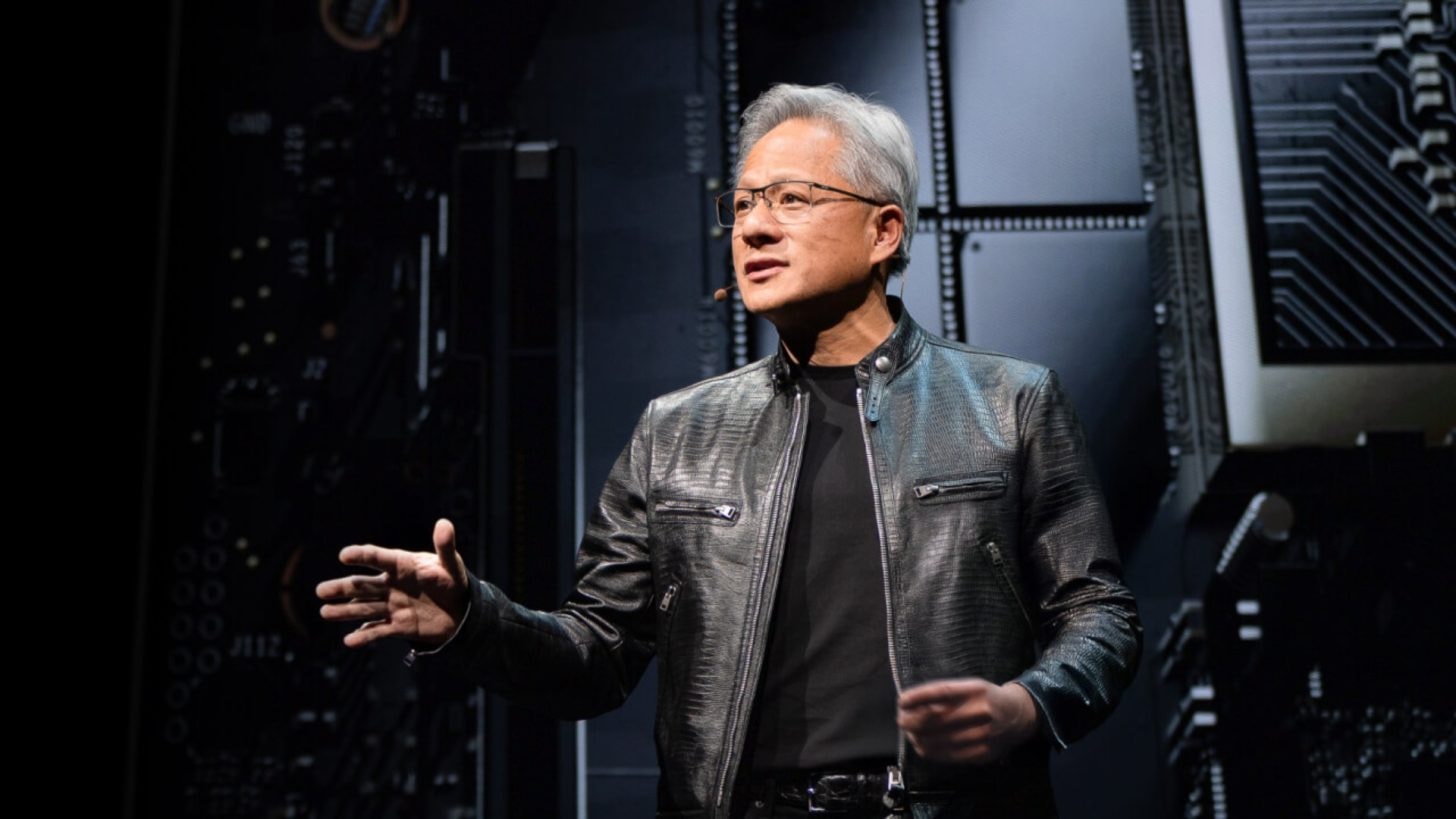

Two years ago at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang predicted that the AI boom would trigger the "largest infrastructure buildout in human history." Looking at the landscape in early 2026, that forecast has moved from speculation to a trillion-dollar reality. Huang’s core argument remains the most significant pivot in the tech labor market: the expansion of AI requires boots on the ground, not just fingers on keyboards.

In his conversations with global financial leaders like BlackRock’s Larry Fink, Huang has consistently argued that the labor market’s focus is shifting toward vocational experts. "It’s wonderful that the jobs are related to tradecraft," Huang noted, specifically identifying a desperate need for plumbers, electricians, and steelworkers.

The $1 Trillion Hardware Tax

The sheer physical demand of AI distinguishes it from the software-only revolutions of the past. Modern GPU clusters are energy-dense environments that generate staggering amounts of heat. This has necessitated a shift from traditional air cooling to advanced liquid cooling systems—a transition that has effectively turned commercial plumbers into "thermal management specialists."

This physical layer is immune to the automation AI provides. You cannot "prompt" a liquid cooling manifold into existence, nor can an LLM troubleshoot a high-voltage transformer at 2:00 AM. Every new data center requires specialized network technicians to install miles of fiber and electricians to manage power delivery systems that are often 10 to 20 times more dense than those found in standard office buildings. Huang notes that this buildout has already consumed hundreds of billions of dollars and is on a clear trajectory to exceed $1 trillion in global investment.

Six-Figure Toolbelts: The New High-Tech Reality

The financial map of the United States is being redrawn by this demand. In hotspots like Loudoun County, Virginia, and the Phoenix suburbs, the race to stand up facilities has sent wages for specialized trades soaring. In these regions, experienced electricians and pipefitters are regularly clearing $120,000 to $150,000 a year, with overtime and "mission-critical" premiums nearly doubling standard union rates.

Trade school is no longer a "plan B" for the tech-adjacent; it is a direct route to the heart of the digital economy. While AI disrupts entry-level roles in the humanities and traditional coding, the titans of the industry are signaling that manual expertise is the ultimate hedge against automation.

The "Day 2" Problem: A Construction Bubble?

However, the narrative of a permanent blue-collar renaissance faces a looming challenge: the "Day 2" problem. While a single data center project may require 2,000 to 5,000 construction workers, electricians, and technicians to build and commission, the operational phase—"Day 2"—requires a skeleton crew. Once the servers are humming, a facility that cost $2 billion to build might only employ 50 to 100 permanent staff.

Critics argue that we are witnessing a massive, temporary construction spike. Once the global "sovereign AI" infrastructure is established—a goal Huang encourages every nation to pursue to protect their own language and culture—the demand for this level of manual labor may plateau. The risk is a workforce that has geared up for a generational buildout only to find a maintenance-only economy on the other side.

Grounding the AI Bubble

Huang uses this physical demand to dismiss talk of an AI "bubble." He argues that the heavy investments in land, power rights, and physical materials are responses to a tangible supply-and-demand imbalance. Currently, demand for high-end silicon remains so high that hardware is often spoken for before the foundation of a data center is even poured.

By framing AI as an infrastructure project rather than a software trend, Huang has repositioned the technology as a matter of national industrial policy. This shift ensures that for the foreseeable future, the most important people in "tech" might not be the software engineers in Silicon Valley, but the electricians in the trenches of the heartland.