The Power Density Dilemma: Odinn’s 14-Foot Answer to Blackwell’s Thermal Demands

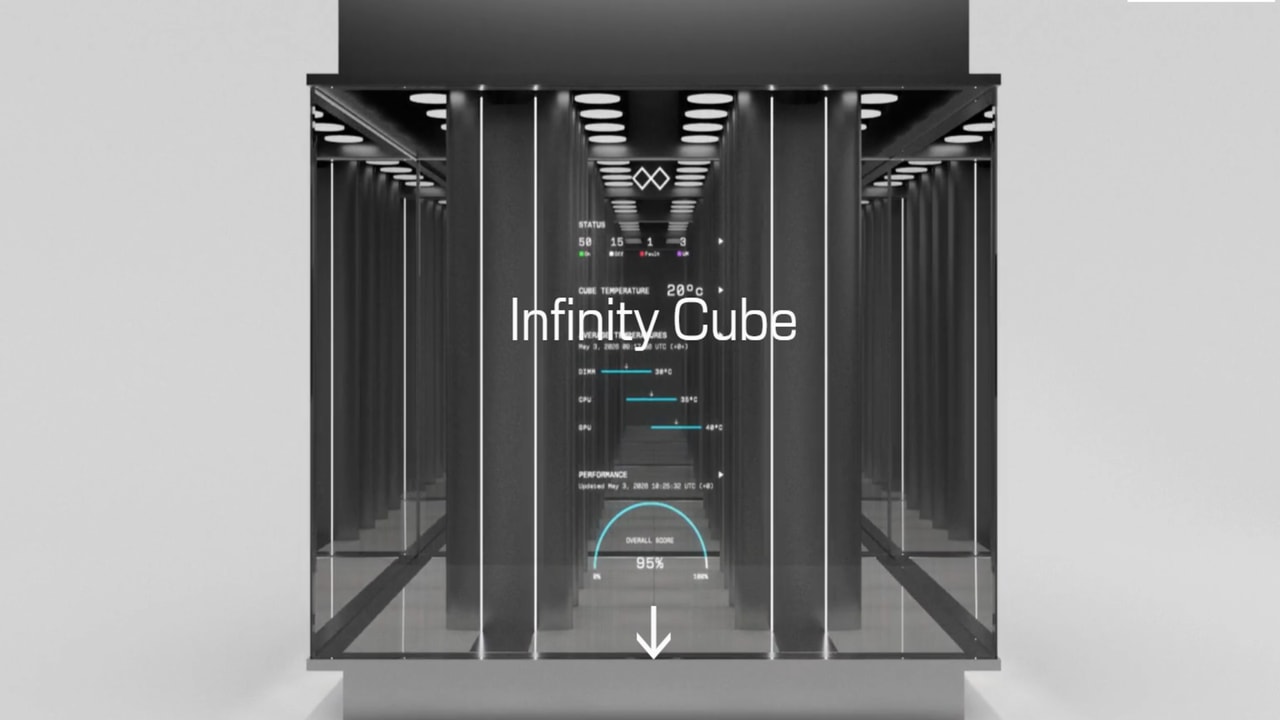

Fitting Nvidia’s Blackwell architecture into a standard data center floor plan has become an exercise in thermal and electrical futility. As the power requirements for a single rack climb toward the 120kW mark, traditional air-cooled facilities are hitting a physical ceiling. Odinn’s "Infinity Cube" attempts to bypass these legacy constraints by condensing 224 Nvidia B200 GPUs into a modular 14-foot structure—effectively turning the data center into a standalone, glass-encased appliance.

The project moves away from the sprawling warehouse model in favor of "concentrated compute." By integrating the hardware, cooling, and orchestration software into a single footprint, Odinn claims it can deliver giga-scale processing power without the need for raised floors or massive external chiller plants. However, the move toward such extreme density raises immediate questions about the industrial infrastructure required to support it.

224 B200 GPUs: The Logistics of Localized Power

The primary challenge of the Infinity Cube isn't just the silicon—it's the electricity. Packing 224 Nvidia HGX B200 units into a 14-foot frame creates a massive concentrated load. Given that each Blackwell-based B200 can pull upwards of 1,000W, the GPU cluster alone accounts for over 224kW of demand, before factoring in the CPUs, networking, and cooling pumps.

While Odinn markets the Cube as a "deploy anywhere" solution, the reality is that a single unit requires a dedicated industrial-grade power drop or a localized substation. To support the 43TB of combined VRAM and the 8,960 CPU cores (provided by 56 AMD EPYC 9845 processors), the system integrates 86TB of DDR5 RAM and 27.5PB of NVMe storage. This density is designed to solve the "infrastructure gap" for organizations that need sovereign AI capabilities but cannot wait for the multi-year lead times typical of hyperscale data center construction.

Glass, Steel, and the Aesthetics of Heat

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the Infinity Cube is its 14-foot glass-encased exterior. In an industry where performance-per-watt usually dictates design, the decision to "beautify" industrial hardware feels like a pivot toward the "AI Factory" as a corporate centerpiece. While the glass offers a high-tech visual for sovereign AI projects, its durability in a high-heat industrial environment remains unproven.

Odinn suggests the glass is part of a controlled thermal environment, but from a practical standpoint, it serves as a visual reminder of the "Sovereign AI" movement—where nations and private entities want their compute power visible and on-site rather than hidden in a remote cloud facility.

Thermal management for this density relies on a closed-loop liquid cooling system. Each "Omnia" module—a 37kg, hot-swappable server unit—manages its own thermal load. This design theoretically eliminates the need for the massive overhead of centralized cooling plants, but it places a heavy burden on the Cube’s internal heat exchangers to reject nearly a quarter-megawatt of heat into the surrounding environment without turning the room into a furnace.

Software Orchestration via NeuroEdge

Managing the internal complexity of thousands of cores and a massive NVLink domain requires more than just high-end plumbing. Odinn utilizes a proprietary software layer called NeuroEdge to coordinate workloads across the entire cluster. This software integrates with Nvidia’s existing AI stack to automate scheduling and deployment, aiming to lower the barrier to entry for organizations without specialized giga-scale engineering teams.

By abstracting the hardware management, Odinn is positioning the Cube as a turn-key product rather than a DIY infrastructure project. This creates a clear trade-off: organizations gain immense density and rapid deployment at the cost of a long-term operational dependency on Odinn’s proprietary software ecosystem.

The emergence of these modular "factories" suggests a fracturing of the AI market. As the hardware becomes too power-hungry for standard racks, the industry is splitting between those who rent time on hyperscale clouds and those who build their own high-density islands of compute. The question remains: can these boutique, sovereign units truly compete with the massive economies of scale found in the giga-scale facilities of AWS or Azure, or will they remain a niche luxury for those who prioritize data physicalist over cost-efficiency?