The Heavyweight Crown: China’s CHIEF1900 Crushes the Gravity Record

If you stood inside the CHIEF1900 at full tilt, you’d weigh as much as a blue whale—or more likely, be flattened into a molecular smear. In the subterranean depths beneath Hangzhou, Chinese engineers have officially powered up the world’s most formidable "time machine": a geotechnical centrifuge capable of generating 1,900 g-tonnes of force. This isn't just a win for Zhejiang University; it is a decisive strike in a high-stakes scientific arms race, leaving the previous record-holder—the US Army Corps of Engineers’ facility in Vicksburg, Mississippi—trailing in a lower orbit of 1,200 g-tonnes.

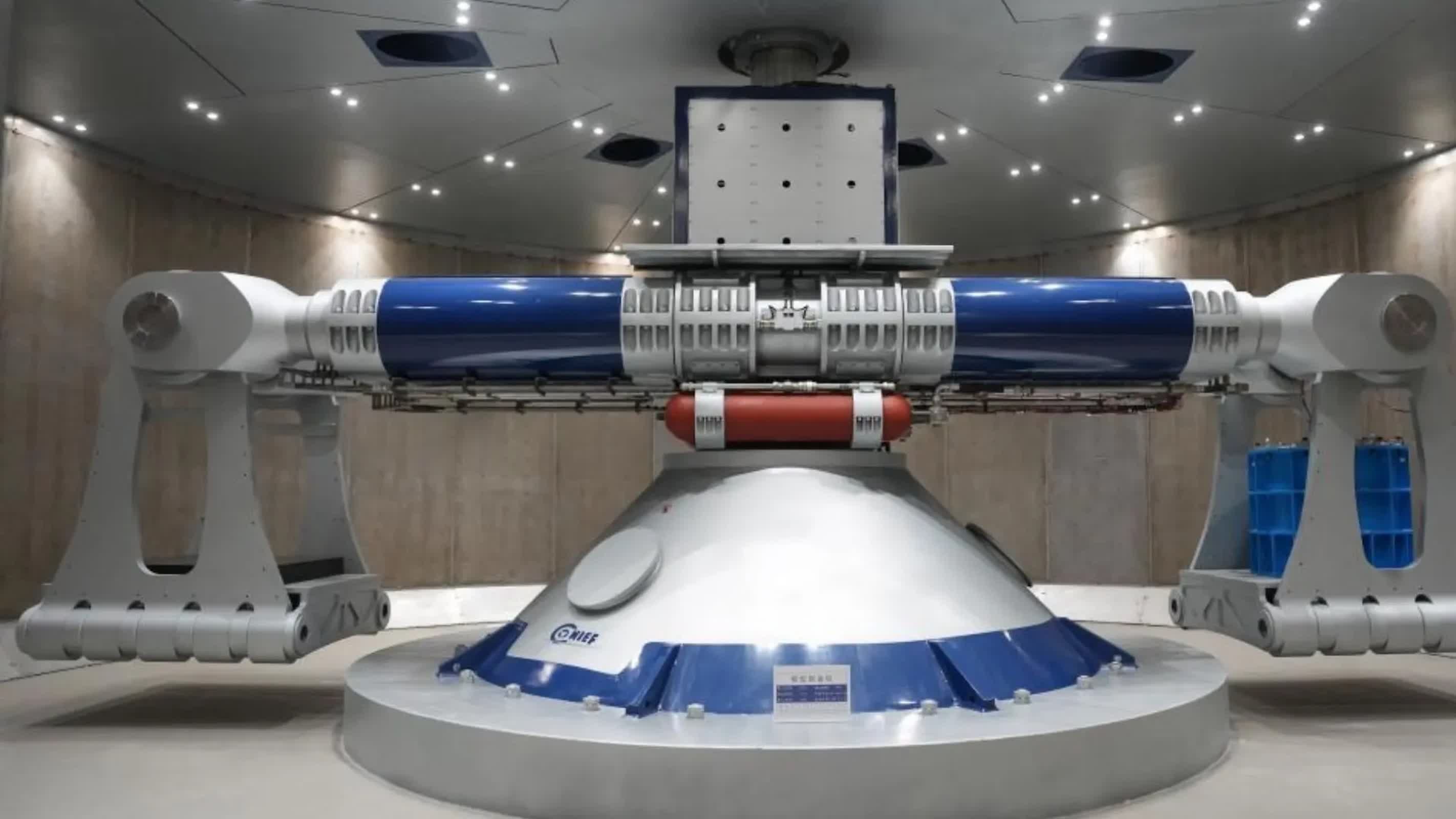

Built by Shanghai Electric Nuclear Power Group, the $285 million facility (2 billion yuan) functions as the flagship of the Centrifugal Hypergravity and Interdisciplinary Experiment Facility (CHIEF). By spinning massive payloads at blistering velocities, the machine multiplies gravitational acceleration to create "extreme states." While a high-end washing machine might hit two g-tonnes, the CHIEF1900 operates on a scale that defies easy analogy, turning the theoretical into the tangible by sheer centrifugal might.

Scaling Reality: Why Gravity Equals Time

The genius of centrifugal modeling lies in its ability to warp the relationship between space and time. In the world of "hypergravity," a few hours of spinning can simulate centuries of geological erosion or pollutant seepage. This is "space-time compression" in its most literal sense. For a structural engineer, testing a 1,000-foot dam is a logistical impossibility—until you place a ten-foot model in the CHIEF1900 and crank it to 100 Gs. Under that intense load, the miniature model's internal stresses perfectly mirror those of the full-scale behemoth.

This capability is the difference between guessing how a dam might fail during a magnitude-9.0 earthquake and knowing exactly where the first crack will form. Beyond civil engineering, the facility serves as a multi-disciplinary crucible. Researchers are already utilizing the machine’s six specialized cabins to solve the "impossible" problems of deep-sea engineering, such as the precarious extraction of natural gas hydrates from the ocean floor. Others are using the hyper-G environment to model how nuclear waste canisters will behave over ten thousand years, or how high-speed rail foundations will settle after decades of relentless vibration.

The Engineering Grit Behind the Spin

Constructing a machine that can swing dozens of tonnes at several hundred miles per hour requires more than just a big motor. The CHIEF complex is buried 50 feet underground to isolate the massive vibrations that would otherwise rattle the city of Hangzhou. The engineering hurdles were immense: the main bearings must support thousands of tonnes of dynamic pressure without seizing, and the internal cooling systems have to combat the tremendous heat generated by air friction as the centrifuge arms "sculpt" the air inside the chamber.

Powering the CHIEF1900 is an exercise in grid management. The energy draw required to accelerate the 18 onboard units to peak capacity is staggering, requiring a dedicated electrical infrastructure. Every component, from the high-resolution sensors to the "shaking tables" that simulate seismic waves while the machine is spinning, must be hardened against forces that would shatter conventional electronics.

A Geopolitical Shift in "Deep Physics"

The activation of CHIEF1900 marks a rapid-fire escalation in China’s research infrastructure. It comes just four months after its predecessor, the CHIEF1300, briefly claimed the world title in September 2025. By jumping from 1,300 to 1,900 g-tonnes in less than half a year, China has signaled that it is no longer content with parity; it is seeking total dominance in "deep physics" and heavy industry simulation.

The gap between the USACE’s 1,200 g-tonne capacity and China’s 1,900 isn't merely academic. Higher g-tonne capacity allows for larger, more complex models and more extreme pressure simulations. This has direct implications for military sovereignty, specifically in the testing of deep-earth bunkers and the development of "bunker-buster" munitions that must penetrate reinforced geological strata. While the facility is technically open to international collaboration—offering a unique platform for biological studies on how plant cells might adapt to the gravity of massive exoplanets—the strategic advantage it provides to Chinese domestic industry and defense is undeniable. In the global race to master the physical world, China just turned the gravity up.